The second trend is the increased prominence of foreign troops and mercenaries in domestic and regional conflicts. …Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki is a central driver of this trend. He has built an entire economy centred on seeking economic rents from mercenaries and military bases.

Source: Al-Jazeera

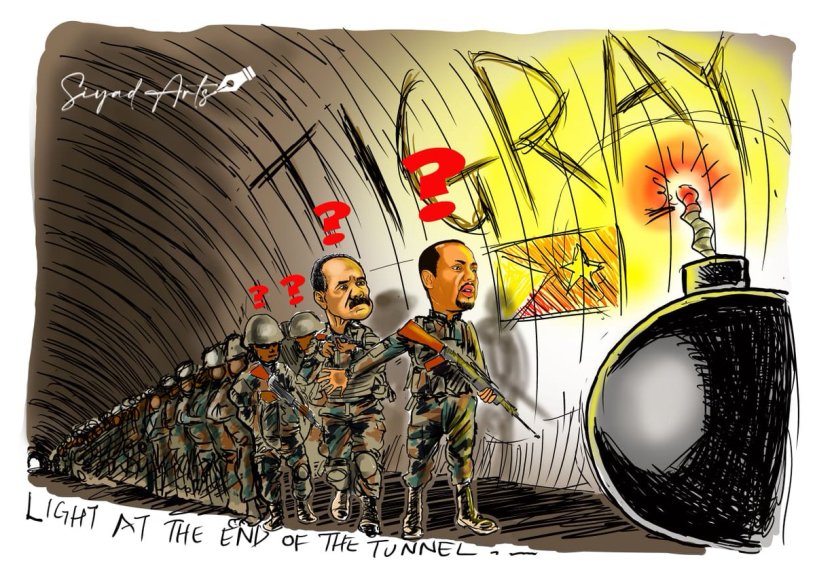

The common political vision of the leaders of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia threatens to throw the region into turmoil.

10 May 2021

![Eritrea's President Isaias Afwerki, Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, and Somalia's President Mohamed Abdullahi pose during the inauguration of the Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital in Bahir Dar, northern Ethiopia on November 10, 2018 [File: AFP/ Eduardo Soteras]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/000_1AQ5B7.jpg?resize=770%2C513) Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, and Somalia’s President Mohamed Abdullahi pose during the inauguration of the Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital in Bahir Dar, northern Ethiopia on November 10, 2018 [File: AFP/ Eduardo Soteras]

Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, and Somalia’s President Mohamed Abdullahi pose during the inauguration of the Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital in Bahir Dar, northern Ethiopia on November 10, 2018 [File: AFP/ Eduardo Soteras]

Three years ago, a wave of political change swept across the Horn of Africa. In Sudan and Ethiopia, popular protests led to a change in leadership and what many assumed were democratic transitions. Ethiopia and Eritrea ended their two-decades-long rivalry, for which Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The peoples of the Horn of Africa were euphoric for what many thought would be a new chapter in the region’s history.

Today, contrary to expectations, mass atrocities, inter-state wars, and autocratic entrenchment have become the defining features of the region. Over the last six months, several international conflicts have (re)emerged, notably between Ethiopia and Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia’s Tigray region, and Somalia and Kenya.

Egypt and Sudan are also threatening Ethiopia over the latter’s plans to proceed with a second filling of the controversial Grand Ethiopia Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile river. Within Ethiopia alone, two significant insurgencies have been launched in this period, while ethnically motivated mass atrocities continue to take place regularly. The Horn of Africa is caught in a spiral of violence where domestic and regional conflicts overlap and fuel each other.

The conflicts and rights violations in recent months are not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern of regional disorder, in which non-compliance with fundamental international legal norms is a central feature.

Four destabilising trends

The first indicator of creeping anarchy in the Horn of Africa today is the recent proliferation of territorial disputes and overall disregard for state boundaries. Eritrea, for example, has begun occupying parts of Tigray in northern Ethiopia and is issuing Eritrean ID cards to residents. Ethiopia is making territorial claims on Sudan’s Fashaga region and in response, Sudanese officials are raising claims on parts of Benishangul Gumuz in Ethiopia.

Within Ethiopia, Abiy has supported the Amhara Regional State’s annexation of parts of Tigray Regional State. Sensing Ethiopia’s weakness, Djibouti recently announced its intention to exploit the Awash river in Ethiopia. At the same time, Ethiopian politicians are publicly making irredentist claims on Eritrean territory. Finally, Somalia and Kenya have exchanged threats over contested maritime space.

While there is nothing wrong with territorial demands made through legal means, what we see is a recent trend of states trying to take over territory by force in order to create a fait accompli. This has led to a contagion effect where one actor’s breach of the norm of territorial integrity encourages other actors to do the same.

The second trend is the increased prominence of foreign troops and mercenaries in domestic and regional conflicts. Abiy Ahmed has outsourced counterinsurgency to Eritrean soldiers in his war against Tigray as well as employed them in the border conflict with Sudan. Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi has also used Ethiopian troops against local opponents in Somalia. At the same time, Somali soldiers have allegedly fought in Ethiopia.

The main problems with these forces are their legal ambiguity, their tendency to commit extreme human rights abuses, and their unique capacity for fuelling inter-communal tensions. Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki is a central driver of this trend. He has built an entire economy centred on seeking economic rents from mercenaries and military bases.

The third problem is the growing disregard for international humanitarian law. Over the last six months alone, Ethiopian and Eritrean forces have engaged in systemic ethnically cleansing, rape, starvation, and massacres on an unprecedented scale. Eritrean troops have also destroyed refugee camps in Ethiopia hosting Eritrean refugees and forcibly returned thousands of them back to Eritrea. So far, this has not had any serious repercussions for the culprits, and when faced with criticism, Abiy and Afwerki have been dismissive.

Finally, today the Horn of Africa is also characterised by a sharp decline in multilateral diplomacy. The regional body Intergovernmental Agency for Development has been excluded from most of the conflicts and peace processes; it has notably been absent in the Ethiopia-Eritrea peace process and the war in Tigray. Instead, leaders have chosen to structure their cooperation and manage conflicts outside of institutional frameworks and through personal channels, which is a significant obstacle for preventive diplomacy.

The domestic politics fuelling regional instability

The destabilisation of the Horn of Africa is primarily a function of the domestic politics of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia. Abiy, Afwerki, and Abdullahi forged the tripartite alliance in 2018 with the aim of moulding the regional order according to their domestic political ideals. The three leaders are opposed to federalism, the accommodation of ethnonational diversity, and institutionalised governance. Instead, they prefer a centralised state under the command of a strongman who rules by fiat.

Afwerki – the godfather of the alliance – has ruled Eritrea without a constitution or a single election for almost 30 years. The source of his autocratic longevity is a universal and indefinite military conscription policy that has contained most of the youth in military barracks and compelled hundreds of thousands to migrate. These conditions have made popular rebellion practically impossible.

In Ethiopia, Abiy was selected by his political party to transition the country to democracy in 2018. However, using COVID-19 as a pretext in June 2020, he postponed elections and imprisoned his opponents. His attempt to concentrate power and suppress Ethiopia’s various ethnonational groups has led to civil war and looming famine.

Abdullahi was supposed to prepare Somalia for its first direct elections in several decades. Instead, he has been trying to centralise power in the federal government, which has resulted in conflict with various regional governments, notably Jubbaland. His term expired in February, and following the example of his regional allies, he extended it for two more years. This has initiated a constitutional crisis and armed conflict, which eventually forced Somali lawmakers to cancel his term extension. He is the first president since the Somali state-building process began in 2004 to try to remain in office after his term expired.

The regional trends that are today destabilising the Horn of Africa emanate from these domestic conditions. The efforts to break federalist forces in Somalia and Ethiopia have led to a spill-over of conflicts across state borders and have fuelled regional rivalries. The members of the tripartite alliance also manage inter-state relations in the same way they govern their domestic politics – they conduct diplomacy through personal channels and resolve disputes through military means.

The alliance’s behaviour is particularly destructive because of its long-term consequences. For example, territorial conflicts, ethnic cleansing, and rape as a weapon of war sow the seeds for inter-generational grievances. In Ethiopia, Abiy’s policies have already revived secessionist sentiments in Tigray and Oromia. And the extent to which Ethiopia will continue to exist as one nation after the war is now questionable. In the last six months alone, these conflicts have displaced more than two million people in Tigray, and the European Union’s envoy to Ethiopia says this may be “the beginning of one more potentially big refugee crisis in the world”.

What is unfolding in the Horn of Africa is a significant threat to international security. Halting the ongoing descent into anarchy requires, first of all, concerted efforts to compel leaders to respect their constitutions.

In both Ethiopia and Somalia, Abiy and Abdullahi must be pressured to enter into a political dialogue with their contenders to reset their democratic reform processes. Secondly, the use of foreign mercenaries in domestic conflicts must be deterred. In particular, verification mechanisms must be established to ensure the withdrawal of Eritrean troops from conflicts across the region. And finally, perpetrators of serious violations of international humanitarian law must be held accountable in order to pave the way for a reconciliation process but also to deter others from engaging in such acts.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

![Eritrea's President Isaias Afwerki, Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, and Somalia's President Mohamed Abdullahi pose during the inauguration of the Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital in Bahir Dar, northern Ethiopia on November 10, 2018 [File: AFP/ Eduardo Soteras]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/000_1AQ5B7.jpg?resize=770%2C513) Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, and Somalia’s President Mohamed Abdullahi pose during the inauguration of the Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital in Bahir Dar, northern Ethiopia on November 10, 2018 [File: AFP/ Eduardo Soteras]

Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, and Somalia’s President Mohamed Abdullahi pose during the inauguration of the Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital in Bahir Dar, northern Ethiopia on November 10, 2018 [File: AFP/ Eduardo Soteras]