Corruption in Africa violates human rights. Why do we tolerate it?

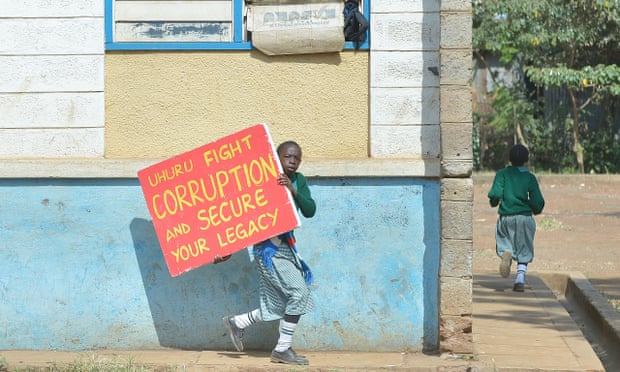

2016-09-17 19:14:55 Written by Anton du Plessis Published in English Articles Read 3444 times  Schoolchildren flee tear gas in Nairobi after police break up a protest. Oxfam says lost tax revenues from offshore holdings cost Africa an estimated $14bn a year. Photograph: Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty Images

Schoolchildren flee tear gas in Nairobi after police break up a protest. Oxfam says lost tax revenues from offshore holdings cost Africa an estimated $14bn a year. Photograph: Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty Images

Corruption is the most neglected human rights violation of our time. It fuels injustice, inequality and depravation, and is a major catalyst for migration and terrorism.

In Africa, the social and political consequences of corruption rob nations of resources and potential, and drive inequality, resentment and radicalisation. Corruption cheats the continent’s governments of some $50bn (£38bn) annually, and stymies successful cities, sustainable economies and safe societies.

This corruption discourages donors and destroys investor confidence, strangling development, progress and prosperity.

Added to that, across the continent, sociopolitical dissatisfaction at corruption provides fertile ground for radicalisation, and some extremist organisations are adept at portraying Islamism as the solution to such injustice.

For example, corruption stimulates recruitment of young Nigerians into the ranks of Boko Haram. In a recent study, 70% of those interviewed in the state of Sokoto cited corruption as a factor driving radicalisation.

By understanding corruption’s full impact and seeing it through the eyes of its victims, we can create new weapons to combat it. This is worth considering as we approach the first-year review of the sustainable development goals. Among them is SDG 16, which aims to reduce bribery and corruption, develop accountable institutions, cut the flow of illicit money and weapons, and strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets.

There are some encouraging signs on the continent. When leaders from countries such as Kenya, Rwanda, Nigeria and Tanzania highlight corruption as a major threat to their countries, then we might just be seeing the final days of impunity. The test now is whether they deliver on these fresh anti-corruption promises in credible ways that take account of human rights.

Human rights are enforced by international treaties, backed by judicial bodies with teeth such as the international criminal court, the international court of justice and regional bodies such as the African court on human and people’s rights. The UN security council and the African Union’s peace and security council can impose sanctions in response to violations of political, economic, social or cultural rights, or to deal with torture, genocide and war crimes. On top of that, countries and international bodies have an obligation to act when human rights are breached.

That’s why so little progress has been made by the UN convention against corruption (Uncac). This global agreement elevated anti-corruption action to the world stage. But Uncac relies on states for implementation, and – unlike global protocols governing human rights – there is no effective sanction for those in breach. An absence of enforcement creates space for corrupt officials and businesspeople to hide without fear of pursuit or prosecution. And there is little political will to change things.

We need to give Uncac muscle by joining the moral and legal dots between corruption, human rights abuses and international crimes. Acknowledging the negative human rights impact of corruption makes it imperative for African states to provide better protection to their citizens. Africans have the most at stake in getting anti-corruption efforts to work, because corruption disproportionately affects poor people.

A more rights-based approach to corruption is a good strategy for both African and European governments. It would mean greater political stability, and provide an environment for sustained social and economic development. This, in turn, would have a positive effect on the drivers of conflict, terrorism and migration.

The human rights community built an arsenal to protect people. Now anti-corruption activists need to do the same.

- Anton du Plessis is executive director of the Institute for Security Studies in South Africa

A joint report by the African Development Bank and Global Financial Integrity found that up to 65% of this lost revenue disappeared in commercial transactions by multinational companies. According to Oxfam, as much as 30% of African financial wealth is estimated to be held offshore, costing an estimated $14bn (£10bn) in lost tax revenues every year.